|

|

|

| |

New York, 15 octobre 2015, photo : A.Başaran |

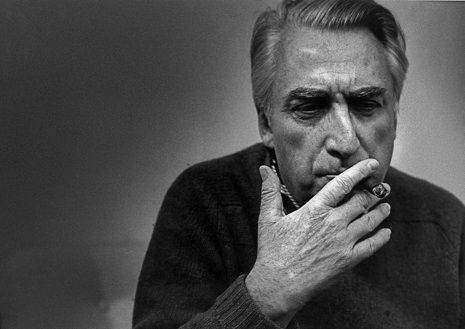

ROLAND BARTHES, l’ÉTRANGER

1. « L’Étrangère » : lignes de

force de l’étrangeté

L’ampleur du 100e anniversaire de Roland Barthes révèle l’universalité de son œuvre, qui touche la singularité de chacun d’entre nous. C’est l’effet paradoxal de l’écriture qu’il a inventée, une cohabitation unique du sens et du

sensible, de la théorie et du style, de la science et de l’imaginaire, et plus

encore de l’expérience de Barthes, qui ne lui donna jamais le nom

de « roman », encore moins d’autofiction, ni même de « littérature ».

Cette expérience, je l’appellerai « Roland Barthes, l’étranger ».

Je me

souviens d’un matin de mai, brumeux et chaud, dans la solitude poisseuse d’un

aéroport surchargé, début mai 1970. Je fais l’achat somnambulique de la Quinzaine littéraire, et dans l’avion

qui vole vers l’Espagne, je découvre son article qui me désigne ainsi : « L’étrangère ». Était-ce moi ?

C’était donc moi ! Incapable de suivre l’argumentation. Ni même de saisir

son effet d’antidépresseur. Seul un souffle salvateur s’emparait de moi hors de

moi, et qui me dépassait. Le dépassement comme possibilité.

Dès 1970,

Barthes fait connaître de l’intérieur cette « étrangeté », une expérience existentielle qui devient un

destin planétaire au XXIe siècle, au gré des crises, des guerres et

de la décomposition de civilisations. Bien plus tard, j’ai pu traverser ce

saisissement et déplier les lignes de

force de cette étrangeté, que Barthes avait minutieusement projetées sur

moi, car elles étaient les siennes, et toute son écriture les met en œuvre.

Selon Barthes

l’étranger, la FORCE de l’étranger ou de l’étrangère tient à sa capacité de DÉPLACEMENT ;

lui-même « change la place des choses », il dénoue les chaînes du

« déjà dit », il détruit le « dernier préjugé », la

mythologie ambiante, c’est-à-dire la « bêtise », l’« autorité »,

la « filiation », la science bloquée par son « signifié »

unique, monologique. Il « n’interprète » pas Racine, Sade, Fourier,

Loyola, Balzac, et d’autres mais bouscule la tradition académique qu’il

renouvelle, lui redonnant vie, ici et maintenant.

Un supplément de liberté

Le travail de

Barthes est – comme il le dit de l’étranger/ère – « entièrement neuf et

EXACT », non pas au sens du « puritanisme scientifique », mais

parce qu’il « occupe EXACTEMENT » – avec précision, justesse et

justice – le lieu de la recherche : son étrangeté inhérente. Ni « technique »

ni « terroriste » (comme on a pu accuser Barthes et ses complices),

cette exactitude, déroutante, nécessite cependant des qualités simples :

- la RAPIDITÉ :

la concision, car « nous (les non-étrangers) allons toujours trop

loin », avertit-il.

- la LUCIDITÉ :

ou plutôt un « supplément de liberté », que les enracinés n’ont pas, et

qui donne à Barthes l’étranger « une pensée nouvelle, pour gagner des

années de travail », hors de la répétition pédagogique, de la complaisance médiatique, ou de l’« inspiration ».

- et le

« regard retourné du LANGAGE SUR LUI-MÊME » : cet estrangement

dans la chair même de la pensée qu’est le langage, ce non-appartenir, ce

« ne pas EN être », rendent l’écriture de Barthes insolite, non

conforme au « discourir » professoral, et pourtant « critique »

à l’endroit de la sémiotique elle-même qu’il a rendue (presque) populaire

- ce « retournement du langage sur lui-même » qui est une « défiguration

productive », tissée de « retours destructeurs », de

« coexistences contrariées ».

Cette discrétion-distinction,

cet apparent retrait gourmand de l’étranger/ère, n’a rien d’ « olympien »

ni de « positif » ni d’« indifférent ». Implicitement,

Barthes l’étranger est « dialogique » avec une ardeur

« sans criaillerie », il fait rêver, tout en explorant vers le

« travail du rêve », et cherche sa « destructivité » à

l’œuvre dans la « fondation » elle-même. Et, de ce fait, Barthes séduit,

mais n’assujettit pas ; sa rêverie corrosive dissuade d’emblée les

épigones. La transmission se fait à force de « frappes » (saisissement

et inscription) et une « germination » : son « développement »,

« au sens cycliste », sourit-il, plutôt que rhétorique du terme, « déclenche

en nous le mouvement créatif lui-même ». Echappant à la « terne

écrivance », son écriture – déplacée, perturbante, inclassable ? – palpe

et fait palper « ce qui la produit et la destine », et le désir déposé en « plaisir du texte », confié en

« discours amoureux », « refuse la propédeutique ». Il

n’est pas pédagogique au sens répétitif de ce métier, il appelle la créativité

du destinataire.

L’autre langue

Est-il en

cela révolutionnaire ? Pas vraiment. Ni militant engagé, ni même un

révolté, Barthes ne se rebiffe que contre la « tarte à la crème » de

la « communication », qui est « une marchandise », dit-il,

et ce bien avant la société du Spectacle, Internet et les réseaux sociaux. En

« dialogiste » méfiant et corrosif, il dénonce le livre

« clair », son « niveau marchand », auquel on veut réduire

la « relation humaine ». Pour lui opposer la « signifiance du

texte », c’est-à-dire sa gestation dans les sensations et la pluralité des sens, la musique dans les

lettres, le coup de dés qui n’abolit pas le hasard.

Ce qu’il

appelle l’ « inculture française » n’a

pas tardé à intégrer institutionnellement l’étrangeté barthésienne dans l’« habitude »

de « clapoter doucement » : honneurs, faveurs, reconnaissancespleuvent

sur lui de nos Ecoles et Collèges. Apparemment conciliant, Barthes se laisse

faire, mais pour mieux pointer – de l’intérieur du « clapotement » – que

l’étrangeté dont il s’agit mobilise contre elle des « raisons

politiques », très exactement le « petit nationalisme de

l’intelligentsia française ». Cette guerre universitaire, en apparence

« culturelle », prend un tour politique : c’est l’increvable Pur et Parfait

Petit Bourgeois Français, en majuscules, est prototype de tous les ennemis de

l’étrangeté, par-delà leurs origines et professions de foi. Car « l’autre langue est celle que l’on parle

d’un lieu politiquement et idéologiquement inhabitable : le lieu de

l’interstice, du bord, de l’écharpe, du boitement : lieu cavalier, parce qu’il traverse,

chevauche, panoramise, offense. » Barthes, le cavalier face au Pur et

parfait Petit Bourgeois Français.

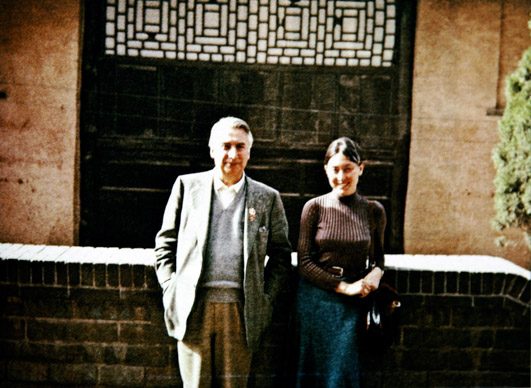

Barthes et Camus

Avant de revisiter

quelques aspects de cette étrangeté dans l’œuvre de Roland Barthes (1915-1980), je vous propose de la penser au regard

de celle d’Albert Camus (1913-1960), associée souvent à l’étranger.

Ils sont de la même

génération, Barthes naît en 1915, Camus, en 1913, et très tôt, la Grande Guerre les fait orphelins de père, ils ont un an. Le père de

Camus meurt en 1914, d’une blessure. A son fils, il ne laisse qu’un seul

souvenir : son profond dégoût devant une exécution. Le commandant de

vaisseau Barthes meurt en 1916, décoré en héros de guerre. Barthes et Camus restent très attachés à

leur mère, ils souffrent de tuberculose, et suivent l’école et l’université de

la République, littérature pour l’un, philosophie pour l’autre. Et tous deux

meurent dans des accidents de voiture.

Étrangers au

« clapotement » petit-bourgeois français, ils nous laissent deux

visions très différentes et, à mon sens, complémentaires de l’étrangeté. À la place vacante de leurs pères

sacrifiés, le refus des idéologies assassines va construire des écritures

rebelles aux hypocrisies sociales.

Camus cultive une ardente

mais discrète fidélité à son père, et, bien que révolté contre l’injustice, il

affirmera qu’il « préfère à la justice sa mère », analphabète et sourde, qui « ne dit

rien » (dans l’Etranger).

Barthes préfère ignorer son héros de père médaillé, symbole d’une fierté trop

consensuelle et guerrière pour cet enfant choyé dans la « chambre

claire » d’une tendresse maternelle exclusive et raffinée, sans issue.

Les analyses accessibles

et sans concession de Camus décrivent la révolte des pestiférés et des justes

dans un style neutre, mais incisif et transitif, qui convient aux journaux, au

théâtre, au roman philosophique et le mène au prix Nobel. Homme à femmes, à la

recherche de la féminité maternelle irréparable, et habitée d’un sens

intransigeant de la justice, humaniste impertinent, anticolonialiste solitaire

et agnostique apaisé, Camus sera l’un des derniers moralistes français.

L’étrangeté de Roland

Barthes, en revanche, se protège dans la chambre claire de la reliance

maternelle, se replie à l’abri des sanatoriums. Dans ce laboratoire fragile, il

développe le « toucher intérieur », l’oïkeiosis de stoïciens grecs, l’art de s’approprier l’intimité de

soi et du tout proche. Pianiste, il s’abandonne à cette volupté dans les

mélodies/mélancolies schumaniennes, que l’écrivain traduit dans le « ut

majeur » de la langue française. Sensitif et indiscipliné, il

déconcerte la superficialité théâtrale du journalisme et la fébrilité du

spectacle philosophique déjà en route. Barthes ne trouvera refuge que dans

l’avant-garde littéraire, un poumon enfin sain pour souffler tout en enseignant. Cet antihéros, en empathie avec le

féminin maternel, soigne sa vie et fourbit son écriture à l’unisson avec

l’homo-érotisme du corps enseignant et avec les désirs de tous les exilés des

certitudes flouées, des identités insoutenables. Aimanté par l’impossible,

mystique du plaisir sans religion, cet homosexuel pudique, blessé par

l’obsession du désir et l’« arrogance des

paumés » (expression qu’il affectionnait), ne s’accomplit que dans la

recherche proustienne, non du

« temps perdu », mais d’une « autre langue » :

lumineuse et toute en nuances, en saveurs et en musiques. Enfin étrangère.

Quand l’Histoire se

fissure, quand les valeurs s’effondrent, et que toute révolte sonne faux en ces

temps d’inquiétude globalisée, nous nous apercevons que la justesse de

l’humanisme camusien ne suffit pas. L’étranger de Camus n’a pas de langage, la

forteresse vide de Meursault s’effondre dans le crime de la douleur aphasique.

Mais Camus l’écrivain réussit à trouver le discours sec, qui nous laisse

désirer son humanisme intransigeant.

Barthes ouvre un autre horizon. Pour

pallier les impasses du « discourir », fût-il porteur des meilleures

intentions humanistes, il est possible de réveiller les logiques dormantes de

la langue et des langages. Libérez leur dialogisme, faites jouer les polyphonies,

entrez dans la chair des mots, rendez l’écriture germinative, les textes

plaisants, détruisez les préjugés et construisez des utopies dans la langue

maternelle elle-même, faites-la autre. Seule une autre

langue peut encore raviver nos intimités étrangères, promises à la soumission ou à

la mort, par ceux qu’elles gênent

ou qu’elles affolent. J’entends l’exaspération de cet appel comme une version complémentaire à

l’humanisme raisonné que Camus a

exercé, et qui reste à refonder.

Aussi de ce Barthes l’étranger, à jamais

inassimilable par le « le Pur et Parfait Petit Bourgeois Français » -

toujours avec majuscules !, de ce cavalier tout

en souplesse et en délicatesse, qui traverse les handicaps de sa santé et

offense la « bêtise » des marchands en communication, quand il

« prend en écharpe » leur conformisme obstiné, je voudrais rappeler trois

apports qui nous aident à respirer,

avec et malgré la survivance des mêmes obstacles politiques qu’il a affrontés.

- L’écriture étrangère à la langue : entre

Blanchot et Sartre

- L’incarnation du sens : la

loquela d’Ignace de Loyola

-

L’intraitable amoureux, à contre-courant

2 . L’écriture étrangère à la langue :

entre Blanchot et Sartre.

Résistant à

la marchandisation de la culture, Barthes, tel le « samouraï » Armand

Bréal, personnage qu’il m’a inspiré, affirme avec force que la culture existe et nous fait vivre, à

la seule condition d’en faire une écriture,

c'est-à-dire de la réécrire, de la critiquer, pour la déplacer sans fin. Il

a opté pour le modeste rôle de lecteur des grands textes littéraires, des

mythes, d’analyste des comportements, de la « bêtise », de l'amour

surtout, et ce sans jamais s'identifier avec « le grand écrivain ». Il

pourfend l’épaisseur des évidences, fait émerger le non-dit, et met au jour la signifiance, c’est-à-dire la

polyvalence du sens, indissociable de la polyphonie interne aux interlocuteurs qui

constituent et interrogent le sens du dire. Deux pôles à la signifiance :

le sur-sens, avec la multiplication

des significations, ou l’éclipse du

sens quand s’écrit la fragmentation de la certitude même qu’un Soi puisse

exister pour le porter.

Avec et

par-delà sa « période » sémiologique, en cette seconde moitié du XXe

siècle, Barthes constate que la modernité est arrivée à la mise en abîme de la possibilité de signifier. Sous le

démantèlement du monothéisme et de ses valeurs, il débusque l’impossibilité du sens unitaire. Celle-ci n’est pas

apocalyptique car elle préfigure également la germination du sens, sa relance et

son renouvellement. Barthes a la conviction qu’une pensée critique,

d’inspiration à la fois sémiologique et littéraire, est en capacité de révéler

cette « mutation » majeure du rapport de l'homme au sens, et il l’enracine dans une

réflexion historique.

Armé de cette histoire du sens, qui va de Loyola à

Flaubert, en passant par Fourier, Sade ou Michelet, Barthes se fait fort de

l’interpréter par l’écriture, qui va contre

la « langue naturelle », laquelle lui paraît servir de ciment « totalitaire ».

Grâce à la signifiance, il s’agit d’atteindre

le corps sous le sens – le corps, tel un secret inapparent mais audible,

demeure l’horizon permanent de ce qu’on appelle la « théorie » de

Barthes.

La sémiologie

de la signifiance contribue ainsi à éclairer la « sublimation »

freudienne, et que j’ai abordé pour ma part en parlant d’un « sujet en

procès ». Ouvrons ses Essais critiques : « L'art est une

certaine conquête du hasard. » S’arracher au

hasard de la naissance, de la biologie et de la dépendance pour ce « coup

de dés » qu’est la préméditation de l’œuvre : n’est-ce pas la magie de

l’Art ? Cependant, l’écriture, dans le « produit dit ‘’œuvre’’, dit

le lieu du sens mais ne le nomme pas ». Barthes l’étranger dissocie

les logiques en présence : l’œuvre ne se réduit pas en sens

« dit » ; l’écriture qui la constitue, « nœud » entre

la pulsion signifiante d’un côté, et la liberté, de l’autre, est l'inépuisable

du sens, accessible uniquement à une infinie interprétation, elle-même

soustraite à l’anonymat du métalangage et exercer par l’écriture polyphonique.

Les textes de L'Espace littéraire (1955)de Maurice Blanchot sont

contemporains de la réflexion de Barthes sur l’écriture, et l’ont certainement

nourri, bien que Barthes affirme d’emblée son originalité. Ainsi, pour

Blanchot, l’écriture est un acte paradoxal, « livré à l'absence du

temps » ; l’écriture est « perte de l'être quand l'être manque »,

« une lumière éblouissante », elle est « sans figure et

infigurable ». Blanchot y déchiffre l’accomplissement du Dieu juif, le

plus exigeant en vérité ; ainsi que le territoire du sublime, le Tout

Autre, extrait du cheminement psychosexuel ; l’espace de l'Absolu, du «

On » majuscule, de l’impersonnel.

Pour Barthes,

l’écriture, parce qu’elle se « dé-saisie » du dire antérieur, est « […] toujours enracinée dans un au-delà du langage,

[…] se développe comme un germe et non comme une ligne, elle manifeste une

essence et menace d’un secret, elle est une contre-communication,

elle intimide. […] Il y a dans l’écriture une ‘‘circonstance’’ étrangère au langage, il y a comme le

regard, d'une intention qui n'est déjà plus celui du langage. Ce regard peut

très bien être une passion du langage, comme dans l’écriture littéraire ; il

peut être aussi la menace d'une pénalité, comme dans les écritures

politiques ; […] écritures littéraires où l'unité des signes est sans cesse fascinée par des zones d'infra ou d’ultralangage [...] ». Écrites en

1953, ces lignes deviendront une méthode d’analyse qui sera appliquée en 1969

dans S/Z.

Cette sémiologie

du « désengagement », ce structuralisme « déceptif » à

force d’être subtil, ne reste pas moins une praxis que Barthes oppose à tous ceux qui seraient tentés de

« pathologiser » ou de « psychologiser ». Les écritures

« différentes » mais « comparables » de Mérimée et

Lautréamont, de Mallarmé et Céline, de Colette et Queneau, de Claudel et Camus,

sont produites par un « mouvement identique qu’est la réflexion de

l’écrivain sous l’usage social de sa forme et le choix qu’il en assume « […] l’écriture est donc essentiellement la

morale de la forme ». Ce mouvement le

rapproche de certaines positions de Sartre, mais Barthes l’étranger apporte une

nouvelle et subtile résonance à l’écriture comme une praxis dans l’histoire. Ainsi, dans Critique de la raison dialectique, Sartre disait que l’œuvre « s’enracine dans la

vie » qu’elle « éclaire », mais « ne trouve son explication

totale qu’en elle-même : et ne révèle jamais les secrets de la biographie ». Si « le

langage est praxis […] et la praxis est toujours langage », leur

détermination – pour Sartre – est de l’ordre de l’idée, de l’option

philosophique, du message. Pour Barthes, elle se situe au contraire, dans le jeu des formes induit par la liberté de

l’écrivain de se placer dans les logiques du sens. Tandis que les « structures

interindividuelles du langage » forment les praxis des hommes dans l’histoire, et orientent l’expérience d’un

Sartre écrivain, tribun et militant, l’écriture-praxis que Barthes ausculte, tout en jouxtant l’ « émiettement »

et la « sémioclastie », « sans figure et infigurable », traverse

le seuil du langage et produit un sens « en plus », un sous-sens, un

« au-delà du langage ». Elle habite l’histoire, comme une praxis infra- et supra- normative.

Serait-elle une « histoire cordiale », dont Barthes parle dans son Michelet : entendez ce

« cordiale » au sens d’un appel à la subjectivité dans ce qu’elle a

de plus savoureux » (autre mot-clé de Barthes), de plus informulable. En somme, l’écrivain qui

vise l’Histoire n’ignore pas la praxis à laquelle pense Sartre, mais elle s’y loge en essayant de formuler les

états-limites de la subjectivité que général l’Histoire préfère ignorer.

1. L’incarnation du

sens : la loquela d’Ignace de Loyola,

le « disponible »

Au Collège de France, en décembre 1968, Émile Benveniste enseignait

que non seulement le langage « dénomme » des objets et des

situations, mais qu’il « interprète » et « génère » des

discours ; en conséquence, la « signifiance » est « un

principe interne » au langage. Avec cette « idée neuve », affirme

le grand linguiste, « nous sommes jetés dans un problème majeur, qui

embrasse la linguistique et au-delà » (Leçon

3 et 5).

Cette immanence de la transcendance, ce

sens non plus externe mais interne à

l’expérience du langage poussé à ses limites que j’appelle

« sémiotique » (pour traverser la surface « symbolique » de

la communication utilitaire),– c’est ce que le

samouraï sémiologue Roland Barthes déchiffre dans les Exercices spirituels de Loyola et incidemment dans son Journal des motions intérieures. Les Exercices s’adressent à quelqu’un de

« désolé », « aux personnes frustes et sans culture », à

l’âme dans sa solitude. Leur but est d’apporter « la consolation » par

le moyen d’une « imagination spatiale » en même temps que « sensorielle »

où « tout le composé de l’âme et du corps » est impliqué La méditation sur l’enfer

du « Cinquième Exercice » nous en offre un exemple. En scrutant les

tourments des damnés dans les flammes, il s’agit de s’identifier à leurs

sensations, mais sans se laisser submerger par elles afin de les redistribuer

en une topographie imaginaire qui est une appropriation, par la pensée, du

débordement sensoriel « nettoyé » en figures « intérieures »

et par conséquent « nominales ». (Entendez :

une mise en mots du débordement sensoriel le plus innommable.)

Loyola

appelle ces méditations, aux confins du senti et du nommé/pensé, « faire

un colloque avec le Christ ». « Colloque extrême s’il en est, qui »

recèle une complexité sensorielle inouïe et fausse compagnie au langage, qui ne

suffit pas. C'est l’expérience de la Passion – dans ce qu'elle a d'innommable

– qu’affronte Loyola. Pour y parvenir, le saint jésuite transite par la

création d’une nouvelle langue. Selon

lui les Évangiles en appellent au vécu subjectif, au fantasme qui habite au

plus intime de l’intime, pour que chacun l’incarne, et que cette incarnation

n’est possible que si et seulement si une nouvelle langue sensible parvient à

l’articuler. Il définit ainsi une nouvelle Chrétienté, dans laquelle la foi du croyant va désormais parler de son intériorité sensible. Ou, plutôt,

chaque intériorité propre rebâtit la

foi : c’est la parole singulière, personnelle, qui constitue le mouvement,

l’énergie de cette expérience religieuse rénovée. Celle qui suscite

l’enthousiasme des découvreurs, des missionnaires, du baroque. Mais aussi celui

des persécuteurs, des inquisiteurs…Il nous revient de reprendre et d’affiner

cette analyse, en ces temps de réveil du « besoin de croire ».

Quant à

Loyola, selon Barthes, son but comprend explicitement un souci psychothérapique :

« se vaincre soi-même, que la sensualité obéisse à la raison ». C’est précisément

dans cette voie si féconde et si risquée, en bord à bord avec

l’extraterritorialité de l’affect, et comme pour se consoler, qu’Ignace invente

la loquela, la « petite

parole », sans équivalent exact en français. Dans le Journal, la loquela évoque

une marque infime, infralinguistique de l’affect, à la frontière indicible entre

le déversement des larmes et l’apparition des mots, là où le vide du déprimé

contacte une sorte de mélodie affectée, certes, mais dégagée des pleurs : « plaisir dans le ton »,

la sonorité vous parle mais « sans faire autant attention à la

signification des mots ». Comme dans

l’enfance ou la psychose, « la loquela intérieure admirable » est une

musique interactive et cependant étrangère au code de la communication.

« Cet horizon zoologique ne donne-t-il pas à l’imaginaire une précellence

d’intérêt ? », se demande Barthes avec intérêt.

Conscient du

danger de la loquela, qui pourrait se

retrancher de la conscience et entraver l’esprit, et après avoir

« introduit en lui la culture du fantasme », Loyola rappelle que cette

« nouvelle langue » implique un « déroulement de la

pensée » complexe, dont le « jugement » divin est loin d’être absent. Mais

il reste « suspendu » et « disponible », engageant Barthes

dans de nouvelles précisions sur le « degré zéro du signe et la solitude

qui résulte de cette ‘’résorption de Dieu’’ »

(à ne pas confondre avec la laïcité qui combat Dieu).

Puisque

« la suspension elle-même marque un signe ultime » , le silence

de Dieu demeure rassurant face à la richesse et la complexité de cette langue,

faite de sensations, de loquela, de

fantasmes et d’hypothèses articulées et d’arbres binaires à l'infini : puisqu’il

y a un « déroulement » de la signifiance, l’assentiment de Dieu est

donné non par un signe, mais par un « retard de signe ». Dès lors, angoisse

de l’exercitant se calme, le silence et le vide ne sont plus menaçants : ils font bel et

bien partie du « déroulement ».

De surcroît, cette suspension de la

réponse divine implique en retour une suspension

du jugement de l’exercitant. Et une « égalité paradigmatique » se

propose à l’exercitant : tous les possibles sont offerts à « moi »,

« je » ne décide pas, « je » suis disponible... comme un cadavre :

« perinde ac cadaver ». Au

contraire de la liberté humaniste, le jésuite ne décide rien, « sinon à

n’incliner à rien » (selon Jérôme Nadal, disciple d’Ignace de Loyola). Un

sujet parlant qui fait sienne la disponibilité totale au déroulement de la

pensée, à tous les possibles logiques : qui dit mieux ?

2.

L’intraitable amoureux, à

contre-courant

En imprimant à sa propre trajectoire ce développement

ignacien des signes jusqu’au sensible pour leur donner, en retour, un nouveau

sens, Barthes réhabilita le discours amoureux, une « inactualité

obscène », dit-il, non sans une perfide ironie. Il fut des premiers, avec

le philosophe Gilles Deleuze par de tout autres voies, à réagir contre la banalisation robotique d'une société

désormais virtuelle.

Distancié et

énoncé en « fragments », le discours amoureux ressource la pensée de

Barthes et rénove un genre mi-classique (Pascal ? La Rochefoucauld ?

Vauvenargues ?), mi-oriental (le zen ?), qui conjoint le plaisir de méditer à

la surprise visionnaire.

Toute

renaissance amoureuse est tributaire d'une révolution de pensée, et dans Histoires d'amour (1983), je me suis plu

à en noter les variations, de l’amour courtois des troubadours à l’amour fou

des surréalistes, en passant par le « Ego

affectus est » de saint Bernard, le libertinage du XVIIIe et

le romantisme à l'ombre de la négativité hégélienne. À son tour, Barthes

ressuscite une nouvelle variante de

la sensibilité amoureuse qui se

déploie à travers deux figures déculpabilisées de l’amour : l’amour homosexuel

et l’amour maternel, dans le sillage de Freud-Lacan-Winnicott, revisités avec

sa lecture favorite, Nietzsche bien sûr - impitoyable tendresse.

En voici la

première figure – l’effondrement amoureux

: « Soit blessure, soit bonheur, il me prend parfois l'envie de m'abîmer. » Pour Barthes, l'anéantissement

de sa maîtrise est la condition de son imaginaire. L'idée, fût-elle encore « fade »,

du suicide colore l’état amoureux : l’amoureux est

« en souffrance » comme un paquet perdu dans un coin de gare. Mais, « délicieux

avantage », ce « ‘Je’, toujours présent, ne se constitue qu'en face de

toi, sans cesse absent. » Souveraineté due

à l’absence, souveraineté... féminine, « Mythe et utopie : l'origine a

appartenu, l’avenir appartiendra aux sujets en qui il y a du féminin. »

Ruse, mais aussi bêtise,

et délire forcément sublime, l’état

amoureux atteint à l’obscénité révélatrice du dénuement au sens de Georges

Bataille : « C'est la forme nécessaire de l’impossible et du souverain. »

Subversion du

langage, l’emprise amoureuse ne rend-elle pas inutile toute

interprétation ? Les Fragments oscillent entre la force du désir qui

submerge et le tissage du déchiffrement qui éveille. En répudiant l’interprète « monologique », Barthes ne

cesse de figurer l’interprétation. La

fougue de Nietzsche se laisse sentir entre les mailles de la discrétion

flaubertienne, la sensation et l’interprétation se confondent dans ce que

Barthes l’étranger appelle un « tel », ou, mieux, un « texte »,

qui est indistinctement l’amoureux et son discours lucide : « En te

désignant comme tel, je te fais

échapper à la mort du classement, je t’enlève à l’Autre, au langage, je te veux

immortel (...). L’ennemi noir du tel,

c’est le Potin, fabrique immonde d’adjectifs. Et ce qui ressemble le mieux à

l'être aimé tel qu'il est, ce serait le Texte,

sur lequel je ne puis apposer aucun adjectif : dont je jouis sans avoir à le

déchiffrer. »

Et seule la jouissance du déchiffrement que proposent les Fragments égale le « ravissement » ou l’ebrietas.

A ce moment du

« développement » au sens ignacien, l’amoureux bascule dans le pathos

du dépassionnement, et/ou du dépassionnement pathétique. Sans intérêt, démodé,

aussi obscène que « le pape sodomisant un dindon » chez Sade, l’amoureux est

tout cela parce qu’il « met le sentimental à la place du sexuel ». Évidemment, c’est

l’amoureux homosexuel qui, dans un sarcasme aussi tendre que ravageant,

revendique ici le ridicule d’un « vieux poupon sentimental » (Fourier). Son discours amoureux, et donc

celui de Barthes lui-même, serait « à

peine un texte », il n’est que « l'amen, la limite de la langue »

: « Moi-même en le disant, fût-ce à travers le clignotement d’une figure,

je suis déjà récupéré. » Dans ce balancement

lui-même, le pathos cependant réhabilité s’affirme,

encore et toujours : « Je prendrai pour moi les mépris dont on accable

tout pathos : autrefois, au nom de la raison (...), aujourd'hui, au nom de la “modernité”... »

La seconde figure, celle de l’amour

maternel, se dissémine en maints endroits des Fragments. De l’enfant

proustien, qui en « veut follement », à l’enfant

winnicottien, qui abrite une « primitive agony » – « nous nous

maternons réciproquement ; nous revenons à la racine de toute relation, là

où besoin et désir se joignent ». L’angoisse

d’amour apparaît dès lors comme la crainte d’un deuil qui a déjà eu lieu.

« Il faudrait que quelqu’un puisse me dire : « Ne soyez plus

angoissé, vous l’avez déjà perdu(e). « E » muet…

« Non-vouloir-saisir », formule

d’inspiration orientale, sera le dernier mot de ces fragments qui n’ont pas

fini de sceller leurs énigmes. Un « NVS » sec – ni bonté ni

renoncement : d’un côté, le monde sensoriel ; de l’autre, « ma

vérité ».

Aimer sans vouloir saisir : telle est la devise de cette nouvelle utopie

amoureuse qui rappelle le ravissement à la manière de Ruysbroeck :

« … âme libre et ivre ! oublieuse, oubliée, ivre de ce qu’elle ne

boit pas et ne boira jamais ! »

Aveu de

frustration, de défaite ? Non. « Le sentiment amoureux est démodé,

mais ce démodé ne peut même pas être récupéré comme spectacle. » Oser dire le

« puéril revers des choses », redonner de la saveur à une histoire

qui a perdu ses valeurs, mais garde encore la « sensation de vérité » : les

« fragments d’un discours amoureux » contre « le

spectacle », en somme.

Je quitte à

regret, avec vous, ce bref voyage dans les textes de Barthes, et vous invite

bien sûr à vous y replonger, vous y trouverez les lignes de force de vos

étrangetés.

Julia Kristeva

Julia Kristeva - Roland Barthes, The Stranger

New York University, Tishman Auditorium

october 15, 2015

|

Cf. «

Comment parler à la littérature », in Julia Kristeva, Polylogue, Ed. du Seuil, 1977, pp. 23-54 ; cf. Roland Barthes, Critique et Vérité, Le Seuil, collection

« Tel Quel ››, Paris, 1966, p. 48.

Roland

Barthes, Essais critiques, Ed. du Seuil, collection « Tel Quel », Paris,

1964 ; « Points-Essais », 1981, p. 218.

Maurice

Blanchot, L'Espace littéraire,

Gallimard, Paris, 1955.

Roland

Barthes, Le Degré zéro de l’écriture, op. cit.,

pp. 8-19. Nous soulignons. « […] L'homme est offert,

livré par son langage, trahi par une vérité formelle qui échappe à ses

mensonges intéressés ou généreux ». p. 59. Entendons : « si

l’écriture est vraiment neutre, si le langage, au lieu d’être un acte

encombrant et indomptable, parvient à l'état d’une équation pure, n'ayant pas

plus d’épaisseur qu'une algèbre en face du creux de l'homme, alors la

Littérature est vaincue. » p. 57. Nous soulignons.

Roland Barthes, Fragments du

discours amoureux, Ed. du Seuil, 1977, p. 15.

|

ROLAND BARTHES, THE STRANGER

1. “The

Stranger”: force lines of

strangeness

The

importance of Roland Barthes’s one hundredth birthday reveals the universality of his work, which affects

the singularity of each of us. That is the paradoxical effect of the writing he invented – a unique

cohabitation of sense and the sensory, theory and style, science and the

imagination – and more importantly, of the experience of Barthes, which will never go by the name of “novel,” much less

autobiographical fiction, or even “literature.” I will call this experience, “Roland

Barthes, the stranger.”

I

remember one hot, hazy May morning in the sticky solitude of a crowded airport,

early May 1970. In my somnambulist

state I bought a copy of the Quinzaine

littéraire, and in the plane flying to Spain, I discovered his article that

named me “The Stranger.” Was this me? So it was! I was incapable

of following the argument. I wasn’t

even able to benefit from the antidepressant effect of it. I felt only a life-saving breath taking

hold of me from beyond myself, and it exceeded me. Exceedance as possibility.

From

1970 on, Barthes made known this “strangeness” from within – this existential

experience that has become a fate of the planet in the twenty-first century,

with its crises, its wars, and the breakdown of civilizations. Much later, I was able to revisit this

shock and unfold the force lines of this

strangeness that Barthes had meticulously projected onto me. Because they

were his, and they were alive in all of his writing.

According

to Barthes the stranger, the FORCE of the stranger inheres in his or her capacity

for DISPLACEMENT; he himself

“changes the place of things,” he loosens the chains of the “already said,” he

destroys the “last prejudice,” the ambient mythology, which is to say,

“stupidity,” “authority,” “filiation,” and science obstructed by its single,

monological “signified.” He does not

“interpret” Racine, Sade, Fourier, Loyola, Balzac and others, but overturns the

academic tradition that he renews, bringing it back to life, here and now.

An additional freedom

Barthes’s

work is – as he says of the stranger – “entirely new and EXACT,” not in the

“scientific puritanical” sense, but because it occupies the space of inquiry

EXACTLY – with precision, accuracy, and justice – which is its inherent

strangeness. Neither “technical”

nor “terrorist” (as Barthes and his accomplices have been accused), this

disconcerting exactitude nevertheless requires a few simple skills:

– RAPIDITY: concision, because “we (non-strangers)

always go too far,” he warns.

– LUCIDITY: or rather an “additional freedom,” which

the well-established lack and which gives Barthes the stranger “a new way of

thinking that saves years of work,” situated far beyond pedagogical repetition,

media-friendly indulgence, and “inspiration”.

– and the “reversed gaze of LANGUAGE UPON

ITSELF”: this estrangement in the very flesh of thought that is

language, this non-belonging, this “not being one of them,” makes Barthes’s

writing unusual, out of keeping with professorial “discourse,” and yet

“critical” to the very place of semiotics that he made (almost) popular – this

“reversal of the language upon itself” that is a “productive disfiguration,”

woven by “destructive returns” and “thwarted coexistences.”

This

distinction-discretion, this apparent retreat favored by the stranger, is not

at all “Olympian” nor “positive” nor “indifferent.” Implicitly, Barthes the stranger is

“dialogical” with an “ungrumbling” ardor; he inspires dreams even while exploring the “work of the dream,” and he

seeks the “destructiveness” at work in “foundation” itself. And as a result, Barthes seduces, but

doesn’t subjugate; his corrosive

reverie immediately dissuades imitators. Transmission occurs through “strikes”

(shock and impression) and “germinations”: its “development,” not in the rhetorical sense but “in the cyclist

sense,” he writes with a smile, “unleashes in us the creative movement

itself.” Escaping “dull

writtenness,” his writing – displaced, disturbing, unclassifiable? – palpates

and makes palpable “that which produces it and destines it;” and the desire lodged in the “pleasure of the

text,” confided in a “lover’s discourse,” “rejects introductory courses.” He is not pedagogical in the repetitive

sense of that profession – he calls upon his addressee’s creativity.

The

other language

Does

that make him revolutionary? Not

really. Neither a committed

activist nor even a rebel, Barthes revolts only against the clichés of

“communications,” which were “commodities,” he says, well before our society of

the Spectacle, the Internet, and social networks. A distrustful, corrosive “dialogist,” he

denounces the “light” book – its “market value,” to which some would like to

reduce “human bonds” – and he opposes the “light” book to the “significance of

the text,” which is to say its gestation in sensations and the plurality of senses, the music in the

letters, the throw of the dice that doesn’t abolish chance.

What

he calls “French unculture” was not slow to institutionally integrate Barthes’s

strangeness into the “habit” of “gently lapping” [l’habitude de clapoter

doucement]: honors, favors,

recognition rained down on him from our Schools and Universities. Apparently conciliatory, Barthes went

along with this, but in order to point out more clearly – from within the

“lapping” – how the strangeness in question mobilizes against itself “political

motivations,” precisely the “small nationalism of the French intelligentsia”

[le petit nationalisme de l’intellegensia française]. This seemingly “cultural” war within the

university took a political turn: the relentless Pure and Perfect French Petit

Bourgeois [le Pure et Parfait Petit Bourgeous Français], in capitals, is the

prototype of all enemies of strangeness, regardless of their origins and creeds. Because “the other language is the one spoken from a place that is politically

and ideologically uninhabitable: the place of the interstice, the border, the

sling, the limp – a cavalier place,

because it crosses, straddles, pans, offends.” Barthes the cavalier facing down the

Pure and Perfect French Petit Bourgeois.

Barthes and Camus

Before

revisiting a few aspects of this strangeness in the work of Roland Barthes

(1915-1980), I propose that we consider it with regard to the strangeness of

Albert Camus (1913-1960), who is more often associated with the figure of the stranger.

They

are of the same generation: Barthes was born in 1915, Camus in 1913, and soon

thereafter, the Great War made them both fatherless, when each was a year

old. Camus’s father died of a wound

in 1914. To his son he left a

single memory: his deep disgust witnessing

an execution. The ship captain

Barthes died in 1916, and was decorated as a war hero. Barthes and Camus remained very close to

their mothers, they both suffered from tuberculosis, and they attended the French

Republic’s schools and universities, one studying literature, the other

philosophy. And both of them died

in traffic accidents.

Foreign

to the French petit bourgeois “lapping,” they left us two very different and,

in my view, complementary visions of strangeness. In the place left vacant by their

sacrificed fathers, the refusal of murderous ideologies would construct

writings that rebel against social hypocrisies.

Camus

cultivated a passionate but discreet fidelity to his father, and although in rebellion

against injustice, he maintains that he “prefers his mother to justice” – a

mother who was illiterate and mute, “saying nothing” (in The Stranger). Barthes

prefers to ignore his father, the decorated hero, the symbol of a national pride

he finds too consensual and warlike. He is a child pampered in the “camera

lucida” of an exclusive and refined maternal tenderness, which offers no exit.

Camus’s

accessible, uncompromising analyses describe the revolt of the plague-stricken

and the just in a neutral but incisive transitive style suited to journalism,

theater, and the philosophical novel – and it won him the Nobel Prize. A ladies’ man in search of the

irreparable maternal feminine, possessed by a resolute sense of justice, an

impertinent humanist, a solitary anti-colonialist and reconciled agnostic,

Camus will be one of the last French moralists.

The

strangeness of Roland Barthes, on the other hand, takes refuge in the light

chamber of maternal reliance, it withdraws into the shelter of

sanatoriums. In this fragile

laboratory, he develops the “inner touch,” the oïkeiosis of the Greek stoics, the art of appropriating the

intimacy of the self and the close-at-hand. As a pianist, he abandons himself to this

sensual pleasure in Schumann’s melodies and melancholies, which the writer translates

into the “C major” of the French language. Being sensitive and undisciplined, he unsettles the theatrical

superficiality of journalism and the frenzy of the philosophical spectacle

already underway. Barthes will only

find refuge in avant-garde literature – finally, a healthy lung to breathe

with, even while teaching. This

antihero who empathizes with the maternal feminine tends to his life and hones

his writing in a manner consonant with the homoeroticism of the teaching body

and with the desires of all the exiles of duped certitudes and untenable

identities. A discreet homosexual,

Barthes is magnetized by the impossible, he is a mystic of irreligious pleasure,

wounded by the obsession of desire and the “arrogance of the wretched” [les

paumés] (an expression he was fond of) – and fulfilled only in the Proustian

search not for “lost time,” but for “another language”: luminous and infinitely nuanced,

flavorful, musical. In a word,

strange.

When

History fissures, when values collapse, and when all rebellion sounds false in

these times of globalized anxiety, we realize that the pertinence and precision

of Camus’s humanism are not enough. Camus’s stranger has no language – Meursault’s empty fortress collapses

into the crime of aphasic agony. But

Camus the writer succeeds in finding the dry discourse that leaves us desiring

his intransigent humanism.

Barthes

offers a different perspective. To

circumvent the impasses of “discourse,” even if it bears the best humanist

intentions, it is possible to awaken the dormant logic of language and

languages: To free their dialogism, to let the polyphonies play, to enter into

the flesh of words, to make writing germinal and the texts pleasing, to destroy

prejudices and to construct utopias in the maternal language itself – all this

makes language other. Only an other language can revive our strange intimacies, destined for

submission or death by those people these strange languages disturb or

terrify. I hear the exasperation of

this appeal as a complementary version of the well-reasoned humanism that Camus

practiced and that has yet to be refounded.

So,

regarding this Barthes the stranger, forever inassimilable by “the Pure and

Perfect French Petit Bourgeois” – still in capitals!, regarding this ever

supple and subtle cavalier who survived the handicaps of his health and offended

the “stupidity” of the merchants of communication as he “sideswiped” their

stubborn conformism, I would like to review three

contributions that help us breathe, with and despite the survival of those

same political obstacles he confronted.

– Writing that is foreign to

language: between Blanchot and

Sartre

– The incarnation of meaning: la

loquela of Ignatius of Loyola

– The irremediable lover, “against the

current”

1. Writing that is foreign to

language: between Blanchot and

Sartre.

Resistant

to the commodification of culture, Barthes, as the “samurai” Armand Bréal, a

character that he inspired in me, forcefully maintains that culture exists and makes us alive only on the condition of making a writing of it, that is to say by rewriting it, by criticizing it, in order to endlessly displace it. He opted for the modest role of reader

of great literary texts and myths, of analyst of behaviors, of “stupidity”, and

especially of love, without ever identifying himself with “the great

writer.” He assails the dullness of

facts, makes the unsaid emerge, and brings to light significance – that is to say, the polyvalence of meaning,

indissociable from the internal polyphony of those interlocutors who construct

and question the meaning of the spoken. The two poles of significance: the sur-sense (or

over-signification), with the multiplication of meanings, and the eclipse of meaning when writing

fragments the very certitude that a Self can exist to bear that meaning.

With

and beyond his semiology “period,” in the second half of the twentieth century,

Barthes notes that modernity has arrived at

the mise en abîme of the possibility of meaning. From under the dismantling of monotheism

and its values, he flushes out the impossibility of a unitary meaning. This

impossibility is not apocalyptic because it also prefigures the germination of

meaning, its revival and its renewal. Barthes holds the conviction that critical thought, inspired both by

semiology and literature, has the capacity to reveal this major “mutation” in

the relation of man to meaning, and he roots it in historical reflection.

Armed

with this history of meaning, that

goes from Loyola to Flaubert, by way of Fourier, Sade, and Michelet, Barthes makes

a point of interpreting through writing,

which goes against the “natural language” that seems to him to serve as

“totalitarian” cement. Thanks to significance, it is a question of

arriving at the body underneath the meaning – the body, like an inconspicuous

but audible secret, remains forever the horizon of what is called Barthes’s

“theory.”

The

semiology of significance thus helps to shed light on Freudian “sublimation,”

and what I myself approached in speaking of a “subject in process.” Let us open Barthes’s Critical Essays: “Art is a certain conquest of chance.” To uproot oneself from the happenstance

of birth, biology, and dependence for this “throw of the dice” that is the

premeditation of the work: isn’t this the magic of Art? Nevertheless, writing, in the “product

called ‘work,’ speaks of the place of meaning but does not name it.” Barthes the stranger dissociates the

logics present in the above sentence: the work is not reduced to what it

“says.” The writing that

constitutes it, the “node” [nœud] made of the signifying drive on the one hand

and freedom on the other, cannot be exhausted by a single meaning and is

uniquely available to infinite interpretation, which escapes from the anonymity

of meta-language and is exercised by polyphonic writing.

The

texts of Maurice Blanchot’s The Space of

Literature (1955) are contemporary with Barthes’s reflections on writing,

and certainly nurtured them, even though Barthes is quick to claim his

originality. According to Blanchot, writing is a

paradoxical act, “surrendered to the absence of time.” Writing is “loss of being when being is

lacking,” “a dazzling light,” it is “without representation and

unrepresentable.” Within it, Blanchot

deciphers the fulfillment of the Jewish God, the most demanding in truth, as

well as the territory of the sublime, the Entirely Other, deprived of

psychosexual development: the space of the Absolute, the “One,” in capitals,

the impersonal.

According

to Barthes, because writing is “un-caught” from the previously said, it is “...

always rooted in something beyond language, [... it] develops like a seed and

not like a line, it manifests an essence and holds the threat of a secret, it

is anti-communication, it is

intimidating. [...] There exists fundamentally in writing a ‘circumstance’ foreign to language, there is, as it

were, the weight of gaze conveying an intention which is already no longer

linguistic. This gaze may well

express a passion of language, as in literary modes of writing; it may also express the threat of

retribution, as in political ones; ... literary modes of writing, in which the unity of signs is ceaselessly fascinated by the zones of infra- or

ultralanguage ....” Written in 1953, these lines will become

a method of analysis that Barthes will employ in 1969, in S/Z.

This

semiology of “disengagement,” this structuralism, which is “deceptive” in its

subtlety, is no less a praxis, because

Barthes opposes it to all those possibly tempted to “pathologize” or

“psychologize” writing. The

“different” but “comparable” writings of Mérimée and Lautrémont, Mallarmé and

Céline, Colette and Queneau, Claudel and Camus, are produced by an “identical

process, namely the writer’s consideration of the social use which he has

chosen for his form and his commitment to this choice... writing is thus essentially the morality of form.”

This

movement toward morality brings him closer to some of Sartre’s positions, but

Barthes the stranger proposes a new and subtle resonance for writing as a praxis in history. In Critique of Dialectical Reason, Sartre

said that ‘the work’ “is rooted in the life” that it “clarifies,” but that it “finds

its complete explanation only in itself: and never reveals the secrets of the

biography.” Nevertheless, if “language is praxis ... and praxis is always language,” their determination – for Sartre – belongs

to the order of the idea, to the philosophical option, to the message. For Barthes on the contrary, the praxis

of writing is located in the play of

forms enabled by the writer’s freedom to position himself within the

multiple logics of meaning. While

the “interpersonal structures of language” form the praxis of men in history and orient the experiences of a writer,

spokesman and activist like Sartre, the writing-praxis that Barthes auscultates – even while approaching

“dissipation” and “semioclasty,” “without representation and unrepresentable” –

crosses the threshold of language and produces an “extra” meaning, a sub-sense,

something “beyond language.” It

inhabits history, like an infra- and supra-normative praxis. Perhaps it is

the “cordial history” Barthes discusses in his Michelet; let us hear

this “cordial” as an appeal to subjectivity, in the sense of more “delectable” [savoureux]

(another keyword for Barthes), more un-formulable. In short, the writer who sets his sights

on History cannot ignore Sartre’s praxis,

but he finds its place by attempting to formulate the limits of the

subjectivity that History generally prefers to ignore.

2. The

incarnation of meaning: la loquela of

Ignatius of Loyola, the “available”

In

December 1986, at the Collège de France, Émile Benveniste taught that not only

does language “name” objects and situations, it also “interprets” and

“generates” discourse. Consequently, “significance” is not transcendent, but rather it is “a

principle internal to” language. With this “new idea,” affirms the great linguist, “we are thrown into a

major problem, that encompasses linguistics and beyond” (Lessons 3 and 5).

This

immanence of transcendence, this meaning that is no longer external but internal to the experience of language

pushed to its limits, which I call “semiotics” – a modality that crosses the

“symbolic” surface of utilitarian communication – is what the samurai

semiologist Roland Barthes deciphered in the Spiritual Exercises of Loyola and, in passing, in his “journal of inner

movements”. The Exercises are addressed to someone “in

distress,” “to crude and uncultivated individuals,” to the soul in its

solitude. Their aim is to provide

“consolation” by means of a “spatial” as well as “sensorial” imagination that

involves “the whole composite of soul and body.” The meditation on hell in the “Fifth

Exercise” offers us an example. In

scrutinizing the torments of the damned in flames, it is a matter of

identifying with their sensations, but without letting oneself be overwhelmed

by them, in order to redistribute them in an imaginary topography that is an

appropriation, by thought, of a sensorial overflow “cleaned up” into “inner”

and consequently “nominal” figures. Loyola

invites his followers to put into words the most unspeakable sensorial

excesses.

At

the outermost bounds of the felt and named or thought, Loyola calls these

meditations “making a colloquy with Christ.” “An extreme colloquy if it is one,

which” contains an unprecedented sensorial complexity and gives the slip to

language, which does not suffice. Such

is the experience of the Passion – of

the unspeakable part in it – that Loyola confronts. The Jesuit saint arrives there through

the creation of a new language. According to him, the Gospels appeal to

subjective experience, to the fantasy that inhabits our innermost depths, so

that each individual incarnates it; but this personal incarnation is possible

if and only if a new sensory language succeeds in articulating it. He thus defines

a new Christianity – one in which the believer’s faith will now speak of his

or her own personal sensory interiority. In other words, each individual interiority rebuilds the

general faith. It is this kind of

language, singular and personal, that will constitute the movement and the energy

of this renewed religious experience – an experience that prompts the

enthusiasm of discoverers, missionaries, and baroque art, but also the enthusiasm of persecutors,

inquisitors, and so forth... Now,

in our modern times when the “need to believe” if reawakening, it is up to us

to resume and refine this analysis.

As

for Loyola, His aim, according to Barthes, explicitly includes a

psychotherapeutic concern: “to conquer oneself – that is, to make

sensuality reach reason.” It is precisely in this very fertile and

very risky way, side by side with the extraterritoriality of bodily affects –

be they suffering or ecstasy –, and as though to console himself, that

Ignatius invents the loquela, the

“little word,” for which there is no exact equivalent in French or

English. In his journal, the loquela evokes a minuscule, infra-linguistic

mark of the affect, at the unspeakable boundary between the spilling of tears

and the appearance of words, where the emptiness of the depressed person makes

contact with a kind of melody, affected of course, but already free of

tears: “Pleasure in the tone,” the

sonority speaks to you but “without paying so much attention to the meaning of

the words.” Between body and meaning, as in

childhood or psychosis, “the admirable interior loquela” is an interactive music, nevertheless foreign to the code

of communication. “Does not this zoological horizon give

the image-system a preponderance of interest?” Barthes wonders interestedly.

Conscious

of the danger of the loquela, which

could split off from consciousness and hamper the mind, and after having

“introduced in it the cultivation of fantasy,” Loyola reminds us that this “new

language” necessitates a complex “unfolding of thought,” in which divine

“judgment” is nevertheless far from absent. But this judgment remains “suspended”

and “available” [disponible], bringing Barthes to make more precisions regarding

the “degree zero of the sign and the solitude that results from this ‘resorption of God’” (not to be confused with the secularism that annihilates God).

Since

the “suspension of meaning and of God itself marks an ultimate sign,” God’s

silence remains reassuring in the face of the richness and complexity of this

language made of sensations, loquelas,

fantasies, articulated hypotheses and binary systems branching to infinity. Since the meaning “unfolds,” God’s

assent is given not by a sign but by its “delay.” The exercitant’s anguish is subsequently

eased, the silence and void are no longer threatening; they are well and truly part of the

“unfolding,” developing, liberating of the divine and from the divine.

Furthermore,

the suspension of the divine response in turn implies a suspension of the exercitant’s judgment itself. And the exercitant is offered a

“paradigmatic equality”: all

possibilities are presented to “me,” but “I” do not decide, “I” am available...

like a corpse: “perinde ac cadaver.” Contrary to the humanist’s

freedom, the Jesuit decides nothing “except to be inclined toward nothing”

(according to Jerome Nadal, Ignatius of Loyola’s disciple). A speaking subject who makes himself

totally available to the unfolding of thought, to the possibility of all logics.

Isn’t this the very experience of writing? What could be better?

2. The irremediable lover, “against the current”

By

transferring onto his own trajectory this Ignatian development of signs toward

the sensory, in order to give them a new meaning, Barthes rehabilitated amorous

discourse – an “obscene anachronism” he says, not without false irony. He was among the first, along with the

philosopher Gilles Deleuze, who took entirely different routes, to react

against the robotic trivialization of a thenceforth

virtual society.

Distanced

and set forth in “fragments,” the lover’s discourse revitalized Barthes’s

thought and restored a half-classical (Pascal? La Rochefoucauld? Vauvenargues?), half-eastern (Zen?)

genre that unites the pleasure of meditating with visionary surprise.

Any

amorous rebirth is dependent on a revolution in thought, and in my Tales of Love (1983), I took pleasure in

noting the variations, from the courtly love of the troubadours to the mad love

of the surrealists, by way of Saint Bernard’s “Ego affectus est,” the eighteenth century’s libertinism, and

romanticism in the shadow of Hegelian negativity. In his turn, Barthes revives a new variant of the lover’s sensitivity that is deployed through two figures of love

ridden of guilt – homosexual love and maternal love – in the wake of

Freud-Lacan-Winnicott, revisited with his favorite reading, Nietzsche, of course

– ruthless tenderness.

Here

is the first figure – amorous collapse:

“Either woe or well-being,

sometimes I have a craving to be engulfed.” For Barthes, the annihilation of his self-mastery is the condition of

his imagination. The idea of suicide – be it still “bland” – colors

the lover’s state: the lover is en souffrance _– in pain, or “in suspense” like a package lost in

the corner of a railway station, or like a corpse, according to Ignatius. But, “delicious advantage,” this “always present I is constituted

only by confrontation with an always absent you.” A sovereignty due to absence, a

sovereignty that is... feminine. “Myth and utopia: the origins have

belonged, the future will belong to the subjects in whom there is something feminine.”

Ruse, but also stupidity, and certainly sublime delirium – the lover’s state achieves the

revelatory obscenity of being stripped bare as in the work of Georges Bataille: “It is the

necessary form of the impossible and of the sovereign.”

As

a subversion of language, doesn’t love’s influence render all interpretation useless? The Fragments oscillate between the power of desire,

which overwhelms, and the weaving of deciphering,

which awakens. By repudiating the

“monological” interpreter, Barthes endlessly figures interpretation. Nietzsche’s ardor can be felt between the braids of Flaubertian

discretion; sensation and

interpretation merge in what Barthes the stranger calls a “thus” or better, a

“text,” that is equally the lover and his lucid discourse: “Designating you as thus, I enable you to escape the death of classification, I kidnap

you from the other, from language, I want you to be immortal... The worst enemy of thus is Gossip, corrupt manufacturer of adjectives. And what would best resemble the loved

being as he is, thus and so, would be

the Text, to which I can add no adjective: which I delight in without having to

decipher it.” And only the delight of the deciphering

that the Fragments offer equals

“ravishment” or l’ebrietas.

At

this moment of “unfolding” in the Ignatian sense of the word, the lover topples

over into the pathos of cooled passion and/or of the pathetic loss of passion. He is without interest, outdated, as

obscene as “the pope sodomizing a turkey,” for Sade, because he “puts the sentimental in place of the sexual.” Needless to say, it is the homosexual

lover who, in sarcasm as tender as it is ravaging, assumes the ridicule of a “sentimental

old baby [poupon]” (Fourier). His lover’s discourse, and thus

Barthes’s own, may be “scarcely a text at all,” only “the amen, the limit of

language”: “uttering it, even through

the wink of a figure, I myself am already recuperated...” As the scales settle, pathos, however

rehabilitated, asserts itself, as

always: “I take for myself the

scorn lavished on any kind of pathos: formerly, in the name of reason [...], today in the name of ‘modernity’[...]”

The

second figure, that of maternal love, is scattered in many places throughout

the Fragments. From the Proustian child who “wants

madly” to the Winnicottian child who harbors a “primitive agony,” – “we mother each other

reciprocally; we return to the root

of relations, where need and desire join.” Hereafter, the anxiety of love appears

as the fear of mourning for a mother’s love. “Someone would have to be able to tell

me: Don’t be anxious anymore, you’ve

already lost him...” Him? Or her: the first love object.

The

last word of these fragments that have not yet finished with their enigmas is

the expression: “Non-will-to-possess,” inspired by some Eastern cultures. A dry abbreviation “NWP” [in French,

“NVS”, non-vouloir-saisir] – neither

kindness nor renouncement: on the one hand, the sensorial world; on the other,

“my truth.” To love without wanting to possess: that

is the motto of this new lovers’ utopia that evokes ravishment in the manner of

the Flemish mystic Ruysbroeck: “... soul at once free and intoxicated! forgetting, forgotten, intoxicated by

what it does not drink and will never drink!”

A

confession of frustration? A defeat? No. “The lover’s sentiment

is old-fashioned, but this antiquation cannot even be recuperated as

spectacle.” To dare to speak of the “childish

underside of things” restores flavor to a history that has lost its values but

still retains the “sensation of truth”: in short, Barthes persists in facing his

“fragments of a lover’s discourse” against the “spectacle.”

Regretfully,

I come to the end of this journey with you into the texts of Roland Barthes,

and I invite you, of course, to re-immerse yourselves in them, where you will

find the force lines of your own strangeness.

Julia

Kristeva

|

|

|

|

|