|

|

Crossroads

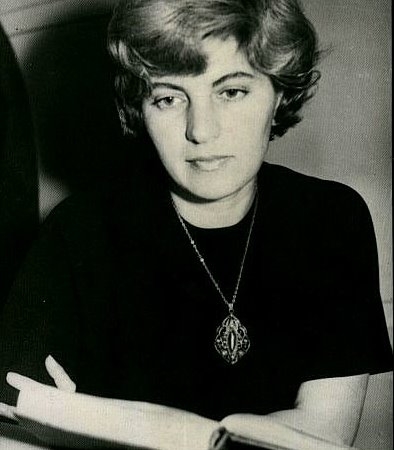

Encounters with Julia Kristeva

Blaga Dimitrova

Simeon Radev, the

great intellectual, diplomat, writer, journalist and public figure, who got to

know the world like only a few of our countrymen, at a personal meeting towards

the end of his life said to me the following in a reverie that was not

befitting him: “If a Bulgarian woman is highly educated, talented, has command

of foreign languages and is beautiful at that, she cannot be but irresistible and unequalled when abroad.”

The old connoisseur

had in mind the women of his own generation: the first Bulgarian woman diplomat

Stanchova, his own wife Bistra Radeva, a painter, whose friendship was highly

esteemed by Paul Claudel, as

well as the younger ones – Dora Ouvalieva-Vallier, an art critic, and the

untimely perished poetess Vessela Vassileva.

Following the example

of Julia Kristeva, I was convinced of the profoundness of this subtle

observation, not only on account of her fame as a structuralist scholar, a

semiotician, a writer, a psychoanalyst – a fame that reached back to the

homeland like the echo of heavenly thunder and music – but above all from

personal encounters.

This subject was the

main topic of a 1991 conference in Vienna, in which intellectuals from the East

and the West participated. Julia Kristeva headed the conference program with

the principal paper-essay entitled “Strangers to Ourselves”.

The overcrowded

auditorium awaited her appearance. Apart from the participants themselves, the

general public was multifarious: intellectuals, students, journalists. The room

proved unable to contain an attention of such enormous proportions. The

renowned lady was to arrive from another conference, in Sweden, I think. The

launching time was already past. The suspense was building up.

All of a sudden, it

seemed as if an electric bolt cut across the atmosphere. A young woman, wearing

a strictly elegant costume, walked in with an air of unique individuality. A

whisper swept along the crowd: Julia Kristeva! She was invited on the podium at

the forum table. She stepped up the small ladder with her exquisite little foot

which so many of her pilgrims yearned for around the intellectual cafes in

Sofia. A step that conquered Paris and then the world itself, not just with

beauty and grace but also with talent, a will to wield an image of her own, and

with incredible energy. She climbed these few steps just as lightly as she

seemed to have topped in one breath the high stages, leading to the summit of

intellectual success. She sat down in a casual fashion and a card with the name

“Julia Kristeva” was placed before her. It truly did look very elated. Yet I,

somewhere amongst the hordes of the people present, felt the terrible burden of

the name Kristeva, the burden of Christ borne on the fragile shoulders of this

woman on the way to her own Calvary. How her secret homeland admirers envied

her without bothering to measure the achievements against the efforts!

She was given the

floor. A pile of sheets in front of her, she commenced talking without reading,

from time to time she only turned the sheets over and went on, musing aloud,

contributing to that long worn-out, yet fascinating subject that she herself

was captivated by - the subject of the Stranger to ourselves. Not a subject but

a fate.

“…And so, when I

pledged my affiliation to cosmopolitism this meant my decision was made counter

to origins and in favor of a transnational and international stance, a

crossroads point at the borders…”

I listened to the

confession of a fate on the crossroads, as if preordained by the very name

Kristeva. I listened to the melody of the French language in her voice that

sent me back to the virginal silence of our first encounter when the

unforgettable Tsvetan Stoyanov, who was probably in love with her, brought her

at home. She was still a student – mute silent, she was but two avid,

all-embracing, wide open eyes. It was there and then that I shuddered at the

power of these female eyes, stark staring into the future.

I listened to the

mellow maturity of her voice after all the years that had passed into the

future that was preordained by her own ambition: “…The first foreigners

reported by Greek mythology were the Danaë women whose adventures are recounted by Aeschylus. They are foreigners in a double sense: they did not speak the language of the

country they fled (Egypt) and were opposed to their Greek origins, as well as

to marriage…”

I listened and

pictured in my mind the old editor of the “Zlatorog” publishing house, asking

me with the zest of an inventor: “Who is Julia Kristeva?”, after he had read

her first

student publication in the Septemvri journal. As well as my own surprise at the originality of this article devoted

to my, as yet, poetic beginnings. I did not know if I should place my trust to

the intuition of the young girl who claimed my verse contained the seeds of

fruitful prose works in the future. Perhaps this prediction of her youthful

voice prompted me to take the risky leap from verse to prose. I owe her

gratitude, which is almost four decades overdue.

And her inspired

improvisation before the Viennese public delved yet deeper into the tragеdy of the subject: “…Following the

Greco-Persian Wars and the Peloponnesian War, the development of trade relations expanded the possibilities of

contact between the ancient Greeks and the non-Greek world… Thus, in Politics Aristotle emphasizes the stoic

notion of cosmopolitism in relation to the polis…”

I listened and

reminisced the time I and Julia parted on her departure to Paris, the city of

her dreams. She was once again but two wonder-stricken eyes – she still could

not believe to having been allowed a short specialization abroad at the

recommendation of Sofia University, from which she graduated with honors

(French Philology). In a time of utter isolation, to grant a young and able

Bulgarian permission to study in a Western country was equal to a miracle. I

gave her the address of a friend of mine who lived there – the first haven in

the foreign city, her first voyage into the immensity of alienation.

“…Unconscious,

displaced, elsewise: being constituted the way we were, we had to gain

knowledge of ourselves, in order to better encompass the universal otherness of

the strangers that we are…”

I listened and

imagined the vicissitudes of this stranger in France. I used to see her on our

occasional encounters in Paris – she: already stepping firmly with her high

heels on the pavement, me: a restless

traveler, short of breath – transiting through freedom, through the foreign

language, through modern culture. Organically infused into French refinement,

Julia was to me an embodiment of joyous modernity. A modern, independent woman,

a scholar, a writer, a Southern flame in the foundry of the French creative

genius: Barthes, Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Philippe Sollers…

“…In a time of

barbaric persecution…” – Julia went on to examine the historical vicissitudes

of the Stranger – “…people were a far cry from the modern mentality and the

right to be different…”

And I recalled the

moving story of her personal participation in the 1968 events as she was

amongst the discontented students and intellectuals. I saw her at the

frontline, side by side with the rebels, while above their heads stood the

slogan Power to the Imagination! (Pouvoir

à l'Imagination!) In

the luxury of the Café de la Rotonde, her favorite restaurant, she

described to me those tempestuous days.

“I would always like

to point out” – Julia announced with a particular tinge in her voice – “that

revolutionary terror is above all set against the foreigners, that there is a

great number of Republican decrees, proclaiming brutal persecution of

foreigners, leading to potential totalitarianism…”

I saw her welcoming

me at her home – the stranger, her or me, in an artistically cozy apartment on

a high floor in the Latin Quarter, treating me to a delicious dinner that was

prepared à la minute after a whole day

of studious work in the library, at the University, at the editorial

office of the Tel Quel journal. I had

the feeling that she achieved everything à la minute with resourceful

talent – a brilliant career, personal contacts with the artists of the age,

book after book, each of which proves and event, change after change, in the

whirlwinds of untamed modernity…

The

lecturer finished her speech without the usual optimistic crescendo that is

characteristic of most speakers of today’s countless symposiums, colloquiums,

conferences and other types of talking-shops. It sounded like a warning: “The

critical mind of the French is lately turning into self-devaluation and

self-hatred…” And at the very end – a pointer towards a possible alternative:

“Against the aggressive nationalisms of the East one could oppose a search for

new forms of community among different and independent individuals.”

With

my entire being I sensed how Julia Kristeva generates a powerful field of

energy around her, which closely and distantly injects the homeland

generations, over time and through the iron curtain, with creative impulses,

despite all obstacles, despite the impossible. Julia achieved the impossible.

She, the woman stranger, opposing the critical and inexorable French mind,

transformed the precipitous foreign terrain into the stepping-stones of her

victorious advance. And the most amazing thing of all: she possesses the valor

to deny herself, to cancel her successes, to overcome her affiliations and to

rush head-on into new risky enterprises. The power of self-denial, of which

Sartre speaks.

After her lecture Julia was plied with questions and she answered each as lively, fresh and inexhaustible as ever. A few Viennese intellectuals and guests invited her to dinner, in order to prolong the intriguing discussion. She invited me as well, her fellow-countrywoman. I preferred, of course, to be with her and declined an invitation to a concert at the Haus Wittgenstein. Julia’s presence, the music of her voice, were to me vital necessities, charging me with that particular spiritual energy which was so defenselessly trampled on in the homeland. The ban on contacts with the world makes us voraciously embittered. At the dinner I had

an even better possibility to convince myself of the truthfulness in the words

of the wise Simeon Radev: “If a Bulgarian woman…” The prominent companions

never took their astonished eyes off Julia, never stopped asking her questions

or objecting her, in order to stimulate her intriguing thoughts. They were

particularly puzzled by her ingenious thesis: the woman is always and

everywhere a stranger – through the roles she is imposed on in marriage,

professional life, society. Not for a moment did the shade of fatigue or

alienation pass over her. One could tell she had a good training. This feast

continued on till late night and I reveled at the sight of an accomplished

person after so many sorrowful examples of hampered and shattered women’s

aspirations.

The two of us wished to

go back to the hotel along the quiet nightly avenues of Vienna. We were

accompanied by Johannes Schlebrügge, a wonderful translator of Julia’s books

into German. We walked slowly, deeply absorbed into a shared inner serenity,

which one attains in spiritual communion. And yet again I listened to Julia’s

voice as she was explicating to the translator some of the particular shifts of

her writing, the peculiarities of her texts. In silence, I was wondering what

the homeland literature had lost with a thinker like her who had bestowed her

talents on French culture. And how much Bulgaria would profit from a name,

which in our country would be suppressed, aligned with the mainstream, poisoned

by mediocrity…

Her books are

translated and cited everywhere across the globe but her homeland. Was it not a

common occurrence in our country to declare as taboo an achievement that

glorified Bulgaria?

As painful as it is,

I have to admit that for a scope of talent such as hers there was no other

choice but exile.

Blaga Dimitrova

(1922-2003)

|

|

|---|